A bit of theory as introduction...

How do you find access to abstract painting?

The abstract painters are generally not fond of ordinary conceptual thinking. They don't like it when people encounter their works in the way one is used to encountering other objects in reality. The very first question that a person usually asks himself when confronted with a previously unfamiliar object for the first time is:

WHAT IS THAT?

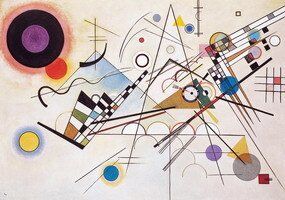

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition V, 1911

Here a person expects as an answer a reasonable explanation how he has to arrange this object into his known world. But this is exactly what the abstract painters want to avoid! Their goal is not to represent or to decorate the already known world, but they would like to point to other worlds, to which one cannot position oneself in such a way as one does in front of an object. The artist may have different ideas about the world he is depicting: for one it is a metaphysical spiritual world, for the other an inner spiritual world, a third may want to accept neither the one nor the other and perhaps speaks of an objective world of forms and colors, which is based only on its own laws.

The abstract artist generally demands that the viewer let his works have an effect on him without thinking about them. He thus demands a contemplative state in the viewer. Only in this way, he believes, can the work speak unadulterated to the viewer. He arrives at this opinion because he himself can only create an abstract work of art from such a contemplative state. His wish is therefore that the viewer should put himself in a similar state as the artist during the creation of his work. Only in this way, he believes, can the work of art convey what the artist has brought up from that world which he wants to represent. If, on the other hand, one were to approach an abstract work of art with the usual terminology, one would close all doors to the true experience of art. There is often a certain agnostic mysticism in the abstract artist, that is, an inkling to penetrate into hitherto unknown realms of human experience, the reality of which he cannot bring to consciousness in any other way than through his art. The abstract painter tries to represent the unspeakable, and therefore does not like it when his art is analyzed by linguistic means.

It would be unwise not to want to follow the artist's advice regarding the handling of his work of art. After all, he himself, as its creator, must know best how to approach the essence of his work. A psychoanalytical or art-historical attitude of observation on the part of the viewer will therefore certainly not be helpful in opening up to an abstract picture. Suppressing ordinary judgment and conceptual thinking while viewing abstract painting must undoubtedly be the first step in approaching this art form. The viewer must first patiently await the effect of the painting in a contemplative state. A side effect of this exercise is that he can learn to apply this contemplative state to other areas of life. It is generally not wise to immediately meet everything one encounters with the full force of one's judgment. A certain restraint of judgment is beneficial in many areas of life, and especially in dealing with other people. Only under extreme, life-threatening conditions of competition is it important to judge particularly quickly. On the other hand, under more relaxed conditions, delaying judgmental thinking can awaken previously unrecognized mental possibilities. Ultimately, however, conceptual, judgmental thinking must begin at some point, because otherwise the person would not be able to place what he has experienced in his usual everyday world. A permanent suppression of conceptual thinking cannot be considered a healthy state in today's man. Therefore it is also necessary to think about abstract art after having first experienced it contemplatively. If one would want to forbid such reflection completely, then one could never work out a natural, relaxed relationship to abstract art. One would then be forced to reject abstract art altogether or to worship it, similar to a religious cult, which one would only be allowed to approach in a state of ecstasy. In order to avoid both extremes, it is necessary to apply the tools of philosophical and spiritual thinking to the phenomenon of abstract painting as well. Through such a conceptual contemplation, the effect of painting is not diminished, since inner silence should continue to prevail in view of the work of art itself; on the contrary, the exact opposite is true: through the possibility of being able to classify abstract painting conceptually in the totality of our world, the contemplative state is even greatly facilitated, because the viewer can then finally face the work of art in a calm and relaxed manner, without having to constantly struggle with the inner resistance of his common sense.

What is representational painting?

Representational painting deals with our everyday perception of reality. The consciousness we have from waking up to going to sleep is awakened by the confrontation of subject and object. Man, as a subject, faces objects that he experiences as objects of his perception. The perception of the objects would be limited to pure sense experiences, if concepts would not arise in the subject, while it faces an object, which refer to the observed object. These concepts are all those feelings and thoughts which refer to the object in the field of perception. Only through the concepts an object becomes a human reality. The perceptions alone would be no more than incoherent sense impressions. The object, which man perceives as reality, is therefore neither a pure concept nor a mere perception, but a unity of concept and perception. The representational painting deals with the representation of this unity. If this unity were exactly the same for every human being, then representational art could never be more than the capture of a transient moment within time, as it is fundamentally practiced in realistic painting.

In classical realist painting, one naively assumes that our perception of reality is based on a natural, universally valid, relationship between man and the environment, and one focuses primarily on the choice of motif and the subtleties of technique when creating a work of art. One is rather less interested in the subjective aspect of the perception of reality. However, the subjective experience of the concepts associated with perception is potentially an individual one, and therefore different for each person, insofar as he is a budding individual. As long as in a society the natural and tradition-bound, conservative life prevails, there is no need for painting other than realistic and also religious painting (we will discuss religious art later). Here, one still lives in a collective world of imagination.

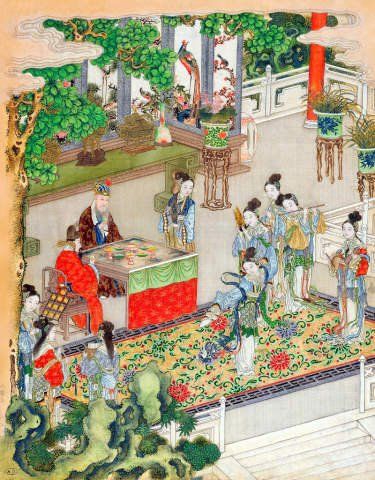

In traditional, standardized arts and crafts, the individual factor is therefore even deliberately excluded completely. One does not represent the objects in such a way, as one could experience them individually, but one follows exact rules of the representation, which are given by the tradition.

However, the more individualism develops in a human culture, the more the urge arises to represent and see the individual, subjective experience represented. Through the detachment of the individual from natural and traditional living conditions, the ability to experience reality individually also increases. However, the more individually an individual experiences his reality, the more he is also torn out of his original, both natural and social, contexts. Thus he gets into a new state of loneliness, which was not possible before. This creates a strong, and often desperate, need for communication between the different, self-contained, individual conceptions of reality. In recent representational painting, therefore, the individual factor is even particularly strongly desired. The personality and the individual form of expression of the artist comes much more to the fore than in earlier times.

Carl Spitzweg, The Poor Poet, 1839

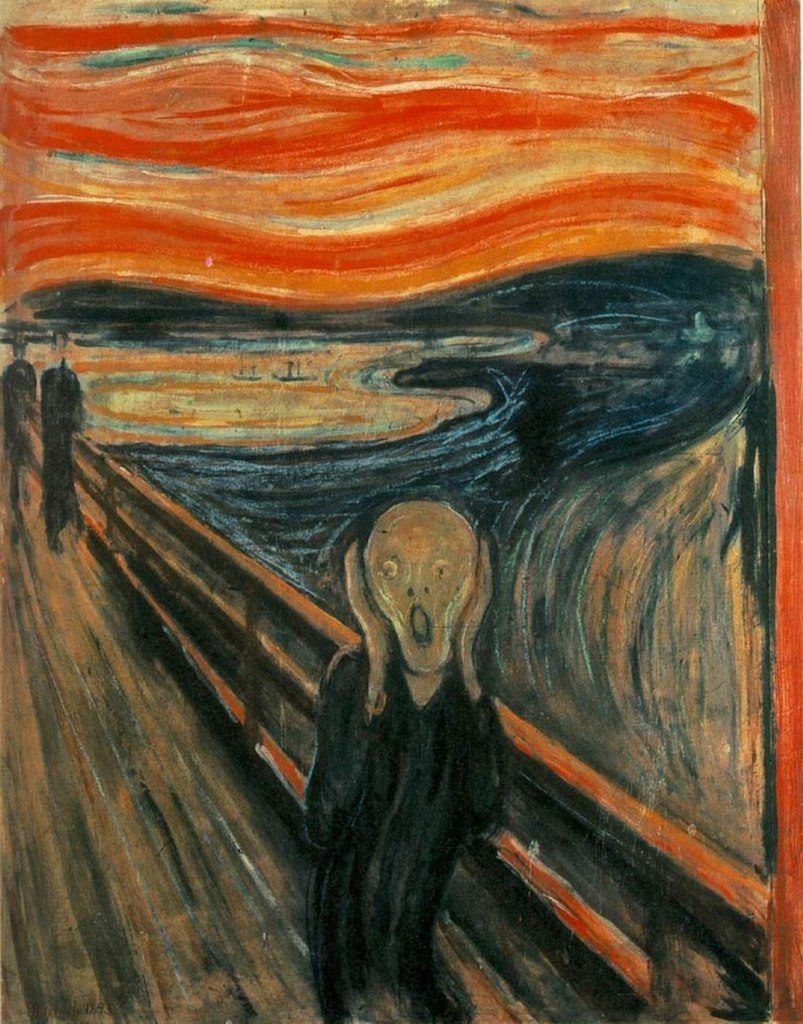

With more intensive exploration of his individual conceptions of reality, the artist can then direct his attention more in one or the other direction of those currents from which the objects he experiences as reality are composed. If he thereby directs his attention more to his own, subjective conceptual world, i.e. his individual thoughts and feelings, which flow towards the sensual perception, then this type of representation is called expressionistic.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

If, on the other hand, the artist directs his attention more to the peculiarities and characteristics of mere sensual perception, then this is expressed in the Impressionist style.

Claude Monet, Garden at Giverny, 1895

Both of these styles, which are mentioned here only as symptomatic examples, explore the connection between concept and perception by no longer being satisfied with the naturally given connection. They both push out of the natural balance between concept and perception and therefore leave the safe ground of realism. In the direction of expressionism, the artist detaches himself more and more from the object and immerses himself into his own world of feelings and thoughts.

Franz Marc, Animal in Landscape, 1914

Likewise, the artist leaves the realm of representational painting as he strives ever further in the direction of Impressionism. The approach to the purely sensual experience, with restraint of the ordering concepts, ultimately leads to a world in which the objects dissolve into forms and colors.

Van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890

Both paths, through Expressionism and Impressionism, lead out of the realm of objective experience.

What is religious painting?

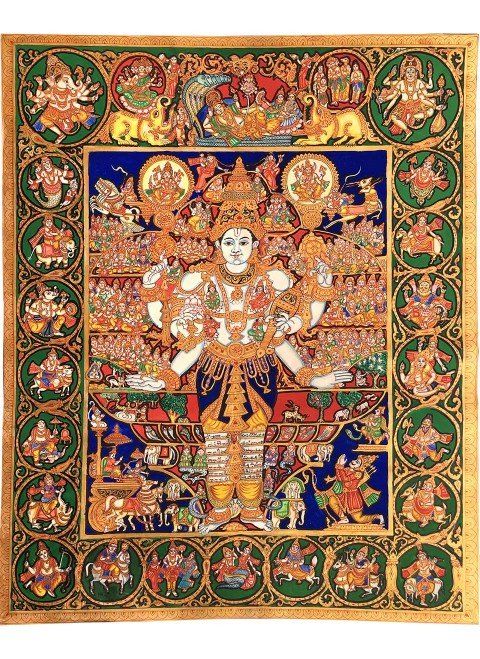

While in more recent times certain currents within the representational art, following an inner urge, pave their way out of the representational world, there was since ancient times an exactly opposite current: a spiritual world that can be experienced only supersensually pushed into the representational world and wanted to be made visible. This task was fulfilled by the cultus in most of the old religions. At that time there was no separation between art and religion. The arts were means of the priests to bring the higher worlds, of which the religions testified, closer to the people. The fact that the experience of art, although dependent on the abilities of the body, is nevertheless a purely spiritual experience and can therefore lift us out of the realm of everyday, representational experience, made art a gateway to a world that is no longer representational. That purely soul-spiritual world is characterized by the fact that in it there is no representational duality of subject and object. Since it is not an objective reality, like our physical world, the heralds of the spiritual world were always confronted with the difficulty, how one could convey supersensible experiences to those fellow men, whose world of imagination is bound only to the objective consciousness. The meditating priest thus formed ideas of a spiritual world, but these ideas did not correspond to sensually easily definable objects. The original impulse for religious artistic creation was thus hidden in the necessity to artificially add a sensually perceptible object to a spiritually experienced idea. It should be achieved that the believing viewer, e.g. of the picture of a deity, could be led to the spiritual truth underlying the picture. The use of pictures, statues and symbols in religious cultus had the task of stimulating in those present those spiritual ideas which the respective cultus wanted to convey to its followers. Therefore, all art was originally entirely at the service of religion. Sacred art was a mediator between everyday perception and a higher spiritual experience.

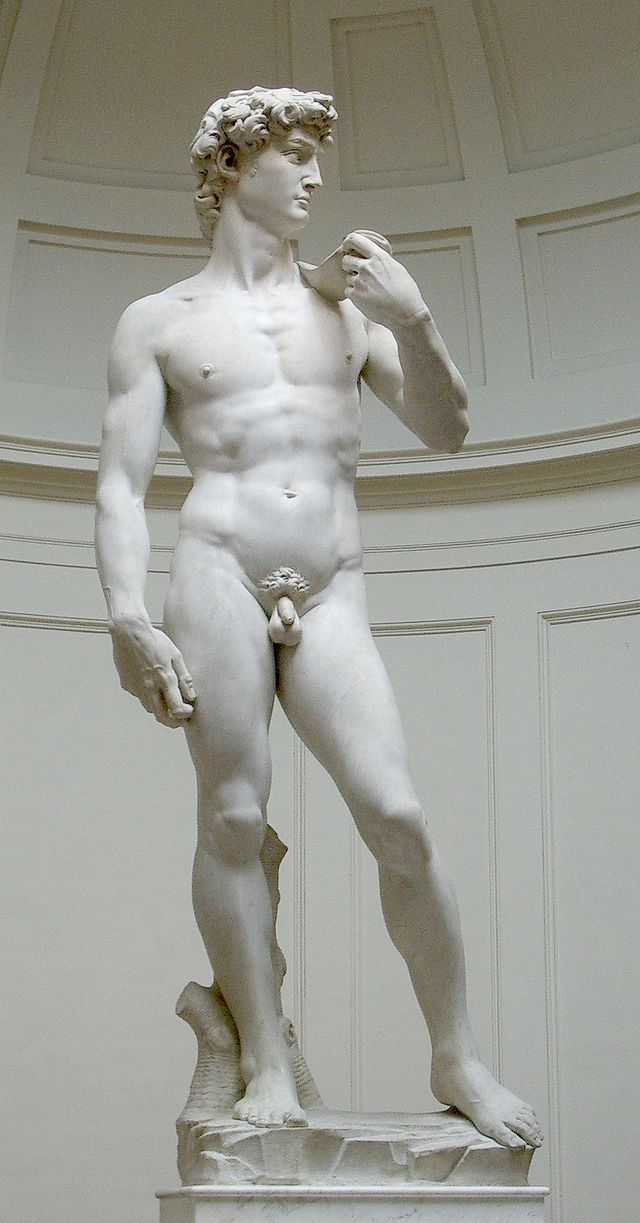

Greek and Roman art is an exceptional case in this respect. Here, representational and religious depiction coincided extremely strongly, because in those ancient humanist cultures nothing was valued more highly than the human body. The representation of the human body was thus at the same time an expression of religious life. The gods were represented in human form. This led to an impressive flowering of all representational art, which was not reduced to religious motifs. In general, in contrast to even older cultures, there was a high esteem for the representationally experienced reality. In that unique cultural period, there was little interest in the afterlife.

This changed again in the following so-called Middle Ages in Europe, which were dominated by the Catholic Church, and in the Byzantine Empire, which existed in parallel. Although Christ had appeared as a man in the flesh, the entire religious imagination in the Christian cultural area was again transferred to a supersensible beyond. To question this circumstance would lead too far here; in any case, painting was again completely absorbed by religion for many centuries. Realistic forms of depiction of man and nature fell into the background, the depiction of religious motifs was the central task of the painters, whereby they had to follow conservative rules and traditions.

What is abstract painting?

Along with the emergence of materialism in the 15th century, a slow detachment of art from religion also began. The first to be rediscovered were the ancient art forms of antiquity.

The Renaissance was seen as a revival of ancient humanism. Although the models of antiquity were gladly followed, completely new styles in the field of representational painting were also created. Perspective and other new forms of realism were discovered.

Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504

Raphael, School of Athens, 1509-1511

Jan van Eyk, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

However, it was still a very long way to abstract painting. The general world of imagination was still determined for a long time either by nature, the human body or by religion. Only in the 19th century, in the heyday of materialism, could the process already described begin, which then expressed itself in Expressionism and Impressionism. For this, during the preceding centuries, first the imaginative life of people had to change fundamentally under the influence of philosophy and natural science. Religious thoughts and feelings had been largely displaced by materialistic and atheistic ideas. The spiritual life, which had formerly drawn its ideas from religious life and a philosophy still spiritually oriented, had given way step by step to a scientifically oriented intellectual life. German idealism had also penetrated deeply into many souls of the educated. What had first lived out in philosophy and natural science now showed its effect in the arts as well. In general, a free space had been created in which man could form his own, earthly human ideas without being hindered by religious authorities and spiritual traditions. Following the example of the philosophers, the painters now also searched for the foundations of painting in an epistemological manner. The painters discovered in their own visually oriented way that reality does not lie ready-made before our eyes, and that we only have to depict it, but that our feelings and thoughts, which we bring to an object, are inseparably connected with the sensually perceived object itself. The painters discovered that there is no such thing as a supposedly objective reality, that is, one that is independent of man. And by pursuing such epistemological questions, they penetrated deeper and deeper into their own world of thoughts and feelings, and in doing so, more unconsciously than consciously, they entered into spiritual realms of experience, where purely mental ideas form pictorial conceptions. One could speak here quite of creative, qualitatively higher, experience worlds, than it is the usual sense world. In former times, when one was still religious, an artist in such a state would therefore perhaps have had a vision of the Madonna, which would have enabled him then to a better pictorial representation of the mother of God. One would then have spoken of a gifted, inspired artist.

Within our materially colored culture, however, the artist encounters here in instead of the Madonna all those abstract ideas which mankind has developed on the basis of materialism. What people think up in abstract theories has, fortunately, no divine creative power in the natural world, but it has quite the power to generate certain imaginary images in the human subconscious. Therefore, in the artistic world of imagination, where ideas are transformed into images, all those ideas are present today which are purely artificial products of human, theoretical thinking. And likewise there are to be found all those feelings which have developed at the same time under the influence of such a thinking alien to reality. Even the ability to create symbols has been captured by the materialistic, abstract thinking. Everything that used to be in the service of a higher spiritual experience has been more and more instrumentalized since the 15th century by a way of thinking that denies the Holy Spirit. This process was unavoidable on the way leading towards human freedom and human self-knowledge. The fundamental freedom of human spiritual creation was thus discovered by modern artists, but at first only under the all-dominating influence of materialism. So, what the modern artists express is definitely a spiritual inner world, which is common to all people who have been educated in the sense of a scientific, materialistic culture. The artists, freed from religion, now began to represent pictorially those ideas which our abstract thinking had developed over the centuries. In doing so, it is always particularly important to them to keep everything representational out of their depictions, because through the representational, the divinely compelling and therefore in a certain respect unfree nature would be brought back into the creative work.

The abstract artists are therefore visualizers of human thoughts and feelings, but not of those thoughts and feelings that man develops when he confronts nature or other external objects, but of abstract thoughts and of feelings that relate to abstract ideas. One could say, then, that the painters repeated once again, visually supported, the entire mental process that philosophy and natural science had undergone since ancient Greece, purely in terms of thought. In doing so, they discovered, as did the philosophers and mathematicians, among other things, the necessity of working with the simplest possible concepts. By working their way through the human imaginary world, artists enter realms of ever more abstract concepts.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VIII, 1923

Up to this point, abstract art could still be called a continuation of expressionism. But when even the last natural and geometric forms have evaporated, then the expressionist artist at some point stands only before a disordered elemental world of colors and shapes.

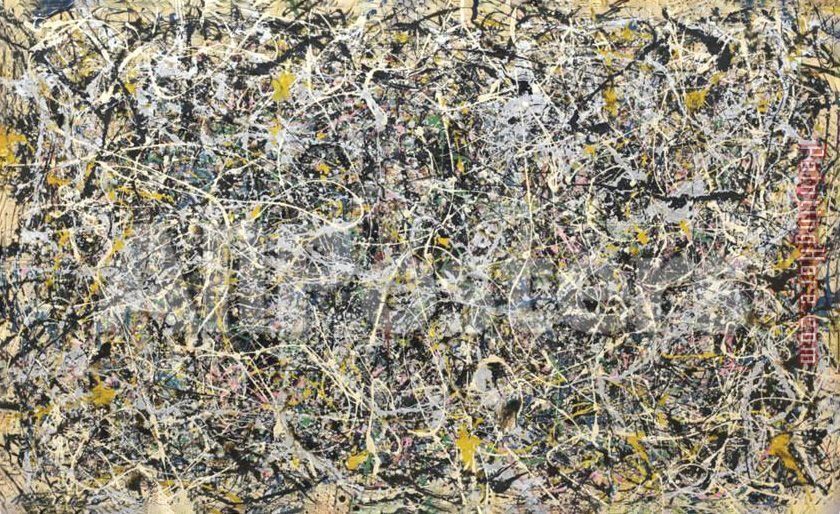

Jackson Pollock, No.1,1949

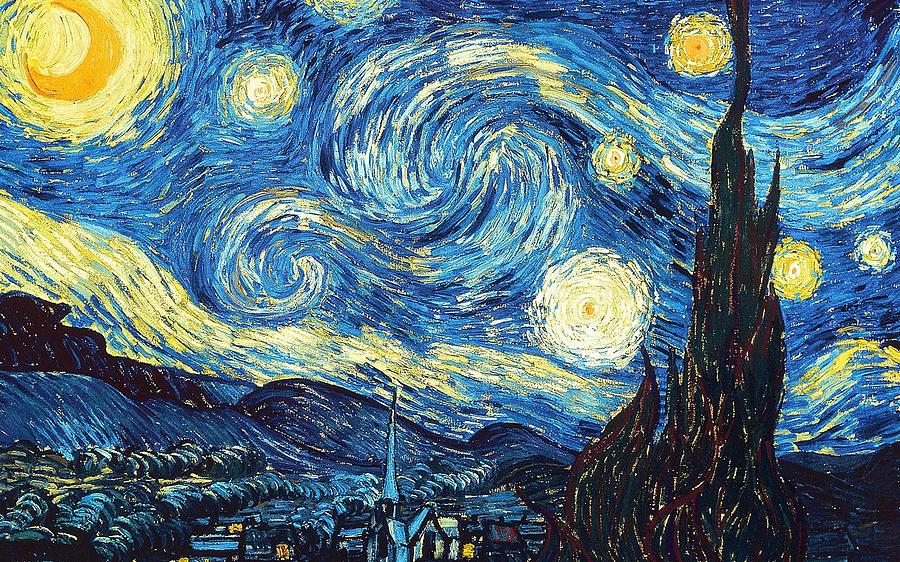

And he could then become aware that painting had already approached this elemental world from another direction, namely when it had striven in the exactly opposite direction, that of Impressionism. In that Impressionist direction, however, art had reached a limit at that time, with a Van Gogh. If Van Gogh had taken the exploration of the mere sensory impression even further to the extreme, then he too would have arrived in a pure world of colors and forms. From his point of view, however, this would have made no sense, because he was concerned with experiencing natural reality, and a nature completely devoid of objects would have been nothing but senseless chaos. Van Gogh could not and did not want to completely eliminate the ordering conceptual world. He still had to retain a certain realism, because he ultimately sought the meaning of his painting in the contemplation of nature.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

The expressionist, abstract painters reach this state of dissolved, incoherent colors and forms, however, from a completely different side! They do not want to see the sense of their painting at all in the fact that their work of art represents any external representational reality. They have consciously practiced to put together colors and forms according to their own abstract ideas, without taking into account the external nature. A further development of the abstract art consists then in this direction in exploring those laws, according to which colors and forms, only out of the forces inherent in themselves, can be joined together.

Through all these efforts, the abstract artists become very good connoisseurs of the forces inherent in colors and forms. They develop a very strong sensitivity for visual connections that no longer needs to be based on anything external. Because of this heightened sensitivity, they gradually succeed more and more in making their most intimate ideas and feelings visible.

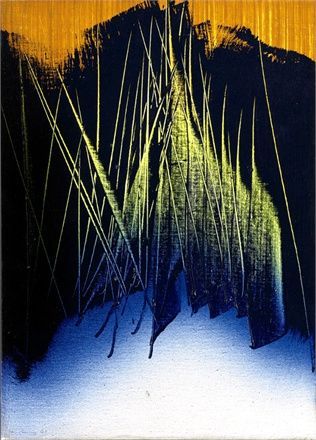

Hans Hartung, 1973

The purpose of abstract painting is thus that the special, both intellectual and emotional, human inner world, which could only develop under the influence of our modern, materialistically oriented world, gets a possibility to become visible here. Abstract art is thus a form of expression of the typical human being of our age, with its desperate urge to establish itself as an independent spiritual being in a universe that it cannot understand.

Life and work of the painter Gerald-Maria Stecker

The Augsburg artist Gerald-Maria Stecker (1945-2018) liked to describe himself as a seeker of God, a visualizer, and a magician. He was obsessed with his art and with the artistic goals he set for himself, without much regard for art history or his artistic contemporaries. Although many of his works can already be attributed to certain well-known styles, he followed his very own path. Even as a very young man he showed an extraordinary talent for painting. He had an innate confidence in drawing and painting expression, which many others have to work hard to achieve. No wonder, then, that he boldly presented himself to the world as an artist at the age of 18. There was never any doubt in his mind that he wanted to be a full-time artist. Although he was active and successful in other fields such as architecture and advertising, he always saw painting as his central mission.

Although he was an atheist, he believed in the reality of the spirit. He could do nothing with the traditional Catholic church faith of his parents, but other religious and spiritual currents that later approached him could not get him on their side either. And there were not exactly few representatives of such currents who were interested in this intense soul. But for Gerald-Maria Stecker there was only one spirit, namely the one he could find in art. And he was not reduced to painting alone. In music or literature, too, he could always find enthusiasm for the spiritual element, which for him always meant overcoming everyday conventions and norms. Personal freedom was a central theme for him. Breaking out of the usual social rules was not just a one-time action for him, but something he had to realize on a daily basis. What drove him was the longing for a genuine, formless encounter with his fellow man. All social rules of conduct were abhorrent to him, and he broke them whenever he had the opportunity. He wanted to be alive, and conventional life seemed to him like a prison from which people looked out on distant reality as if through a window. In all areas of life, he was concerned with removing the obstacles between himself and an authentic experience of the world. And he demanded the same from every person he met, without much regard for their consent. His stubborn behavior was not restrained by anything. Wherever he appeared, one could be sure that he would not go unnoticed.

This whole urge for authenticity, this manic will to get to the origins of life, expressed itself in his art by working systematically in the direction of abstraction. The entire representational reality seemed to him to be something predetermined, given, which he felt above all as a constriction of his individual freedom. He wanted to discover the original sources of reality, but was not inclined to be satisfied with already existing explanations. He wanted to explore the primordial sources of reality on his own, and the supreme tool for this seemed to him to be painting. Painting was for him, as for all painters, a visually visible thought process. For him, as for most modern painters, the creative process did not consist of laboriously translating theoretical thoughts, which one usually formulates in language, into pictorial forms. The ideas and thoughts emerged in him directly in pictorial form. He saw all his pictures mentally before he painted them. He liked to say that he ultimately painted only very few of all those pictures that he used to see. So his paintings were only the final result of a long meditative state of preparation. This was also the reason for his certainty in the form of representation. He had to paint only what he had already seen. Also in other fields of art, like music, the most creative artists are characterized by this talent. Even in the field of natural science, inspiration is not infrequently the basis for the greatest inventions. Of course, these inspirations must then be joined by a technical skill that can only be acquired through diligent practice.

As a man who wanted to stand fully in the middle of real life, he was not seriously interested in philosophical abstractions and scientific theories, except to discredit them as useless. He therefore did not fall into the temptation, as scientific theorists like to do, of wanting to take a great leap directly to the supposed source of all being. In painting, such an approach would correspond to minimalism, which wants to deal directly with fundamental colors and forms. Gerald Maria Stecker, on the other hand, understood that a person who wants to explore the world on his own can only begin where the starting point of his search is, that is, with the human being himself.

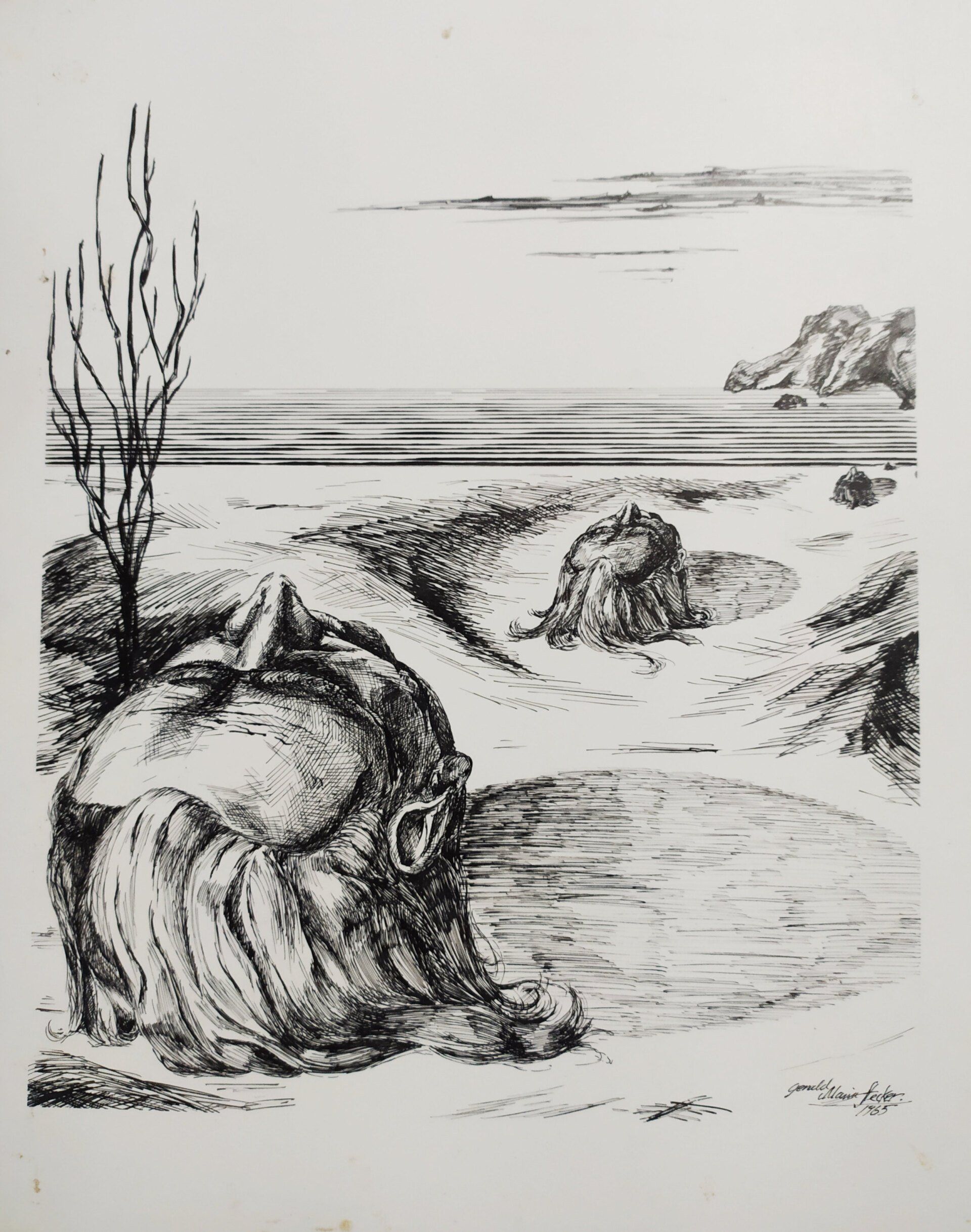

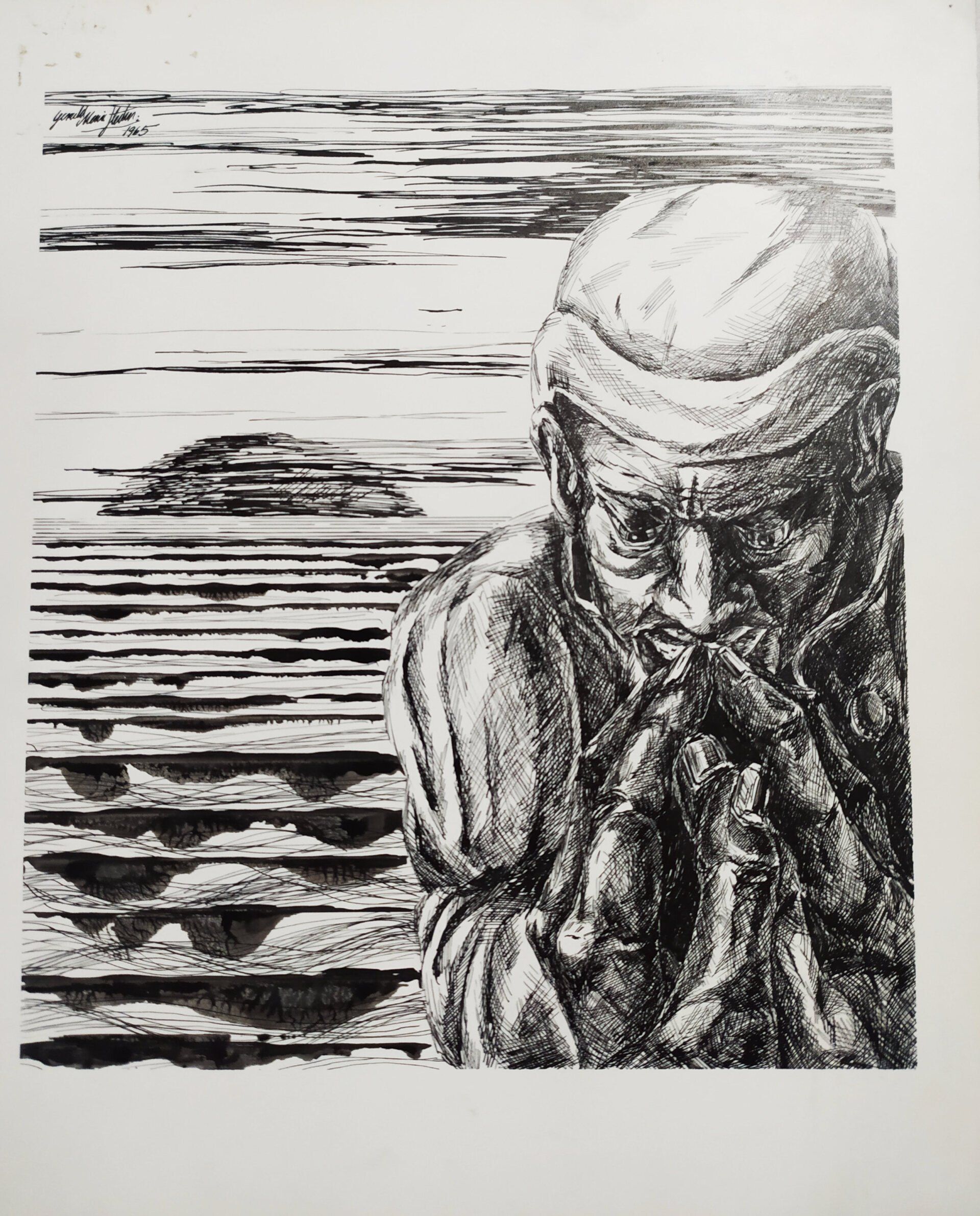

Phase 0 : Realism and Surrealism (1964-1966)

From the very young Gerald-M. Stecker we have a few surrealistic works, some nature studies and a self-portrait, which already announced great talent for painting and drawing.

Phase 1 : Synthetic Cubism (1967)

After some surrealistic works, his first longer creative phase (1) was therefore completely concentrated on the human being, as he gives himself to us in daily life. However, he did not look at this person realistically, but with the prismatic gaze of a cubist. One can clearly assign this first phase to Synthetic Cubism. The expressionist element was still strongly restrained in the beginning and only showed itself in the imaginative background structures and color schemes, which were purely emotionally determined and could not be derived from any logical constructivism. The coloring and the overall mood of the paintings can rather be classified as impressionistic. At that time, he was concerned with creating a harmonious overall impression.

G.-M. Stecker, oil on canvas 96cm x 60cm, 1967

Phase 2 : Cubism (1967)

In a second phase (2) his subjective relationship to his fellow men already became more prominent, which led to the fact that he always depicted people with extremely distorted body proportions. In addition, a certain symbolism is noticeable in this phase, which points to the social relationships between people. Thus, one can clearly feel how the expressionist element is becoming more noticeable. Nevertheless, the Impressionist sensibility remains recognizable in all non-anthropomorphic areas of the paintings. One can generally classify these works as cubism.

G.-M. Stecker, oil on canvas, 60cm x 55cm, 1968

Phase 3 : Surrealist Cubism (1968-1971)

In his third longer creative phase (3), Gerald-Maria Stecker made a creative leap that cannot be derived directly from the previous phases. The only thing he retained was the cubist approach in the depiction of man, but in a completely new way, which is not found as a style in art history, except perhaps in Pop Art. At the same time he makes a leap in the direction of minimalism and surrealism. His subjective opinion of his fellow human beings expresses itself in an even clearer symbolism than before, which was expressed in typification. Whereas before he had been interested in the entire human body, he now reduced the human being to stylized head males and females. The heads and limbs come dominantly to the fore. What stands out is the theme of loneliness and spiritual emptiness. Gerald Maria Stecker himself spoke of socially critical images. One could perhaps speak of a Surrealist Symbolism.

G.-M. Stecker, oil on canvas 80cm x 80cm, 1970

Phase 4 : Impressionist Symbolism (1972-1973)

This phase was followed by a further phase (4), in which he partially retained the minimalist approach, but again achieved a freer use of colors. In the representation of the human being he carried out an extreme simplification. He now depicted him like a single-celled organism or an amoeba. The form is reminiscent of the previous phase. The theme of loneliness and forlornness continues to emerge clearly. In the vast areas between the human germ cells, he explores the interpersonal relationships with a delicate abstract impressionism. A certain surrealist element remains here as well. To distinguish this phase from the previous one, it could be called Impressionist Symbolism.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 80cm x 80cm, 1972

Phase 5 : Metaphysical Abstract Art (1974-1982)

In the subsequent phase (5), which produces different styles, abstract impressionism became independent and freed itself completely from the representational.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 80cm x 100cm

Where Cubism appears, it only serves to represent abstract connections. A certain tendency towards geometric symbolism is already evident at the beginning of this phase, with the above image that the artist classified as his first abstract painting.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 100cm x 125cm

The representation of the physical form of man hereby fell away completely and was never to return. Gerald-Maria Stecker's interest shifted entirely to the background of human life and nature in general. He wanted to penetrate into the origin of all life. In doing so, he discovered the interplay of two contrary creative forces, which he used to call Ratio and Pathos. Ratio and pathos were for him the two original forces from which all life must have developed. Ratio was for him the original, creative intellectual life, pathos the original emotional life lying behind everything. He had thus clearly entered the metaphysical realm in terms of painting. One could therefore also speak of Metaphysical Abstract Art.

In this metaphysical realm of imagination he tried, with different approaches, to explore the connection between primordial feeling and primordial understanding. He himself called this phase "epistemological works". In the same years he also wrote a philosophical paper with the title "A Primordial Way of Seeing".

Clearly, pathos seemed to him to form the primordial ground of all being. For him, this was the realm that Van Gogh would have entered if he had taken his Impressionism to the absolute extreme. He suspected behind all being a non-objective world, a pulsating force field, which, however, is not formless. The forms of that force field, however, can only be experienced passively, and are therefore to be classified entirely in the realm of emotional sensation. The representation of that seething background of all reality meant for Gerald-Maria Stecker his final entry into pure abstract painting. The exploration of that realm was later to occupy his entire attention. In this phase, however, which was also for him personally the center of his life, he was insistently occupied with the connection between that primordial world of feeling, the pathos, and the primordial mind, the ratio, which confronts it. As has been explained in the introduction, our human reality results from the connection between concept and perception. Gerald-Maria Stecker identified the concept-forming power with the human mind and recognized the active creation of forms as its primal property. At the same time he identified the perceptive faculty with the human feeling and recognized as its primal property the passive suffering of impressions. Artistically, this first manifested itself in compositions based on squares.

Although he classified himself as an atheist, the idea of a metaphysical primordial being, which had once created the first rational primordial forms in that metaphysical world, lived in him. Therefore Gerald Maria Stecker called himself a God-seeker. He tried to penetrate into the primordial concepts of God and came across two primordial forms, the bow and the angle, which represented for him the feminine and the masculine, from 1978 on. In the artist's metaphysical world of imagination, a primordial being thus creates the primordial feminine and the primordial masculine by opposing ratio to pathos. At first, the entire world of sensation covers itself with a white veil. But the underground shimmers through the white covering. To depict this, Gerald-Maria Stecker used elaborate glazing techniques. In certain places, one can see through the white veil to a world beyond.

As the creative process continues, the white world of ratio begins to form all kinds of shapes until finally the angles and arcs crystallize. When this point was reached for him, the artist could then return to a theme that had dominated his work from the beginning: the interrelationships between living beings, and in particular, the interplay between the masculine (angles) and the feminine (arcs). This theme he now explored on a purely abstract level.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 163cm x 160cm, 1981

Many artists would have been content at this point to spend the rest of their lives executing this theme in endless variations. After all, he had already achieved what is the goal of every artist: both his style and his subject were new and unique in art history. It was already the second time in his life that he had reached such a point. Phase 4, with its head men, had already been a real novelty stylistically. But it did not correspond to the stormy character of a Gerald-Maria Stecker to remain at the same point! Therefore he looked again for a completely new form of expression. In his private life, this moment coincided with his move from Germany to Italy, to Tuscany.

There were now two paths he could take. One would have been the further development of the geometric world of forms. He could have explored, after angles and arcs also other geometric forms painterly. There are certain approaches to this in his paintings, but ultimately this was not the path he chose. As a great admirer of Van Gogh, he ventured into pure pathos, into the abstract world of forms and colors. In doing so, he finally left the safe ground of rational thinking. What remained was only himself as a human being, in the face of an infinite world that could only be grasped emotionally.

Phase 6 : Abstract Expressionism (1983-1990)

In the first period (until 1986) of this phase (6), which in some respects can already be assigned to Abstract Expressionism, the angles and arcs still sometimes appear, but no longer strictly geometric and also not as separate objects, but united in a single form. He himself spoke of a "dissolution of the geometric elements.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 150cm x 150cm, 1983

Although the expressionist element is dominant, in this phase, and also later, there are always pictures in which the artist expresses himself in an impressionist manner. An interplay can be observed between the purely passive suffering of impressions, and the subjective reaction to these impressions. This reaction, however, never goes further than the aforementioned forms, which arise from a fusion of angles and arcs. In the interplay between the subject of the painter and the world of colors and forms, he largely restrains his concept-forming power. He was primarily concerned with the experience of an objective world, precisely that metaphysical world of pathos which he had recognized as the primordial basis of all existence. From 1987 on, he was increasingly concerned with the abolition of any representational possibility of interpretation. He searched for the "abstract in itself" and he spoke of "images before the images".

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 180cm x 150cm

Phase 7 : Abstract Realism (1991-2018)

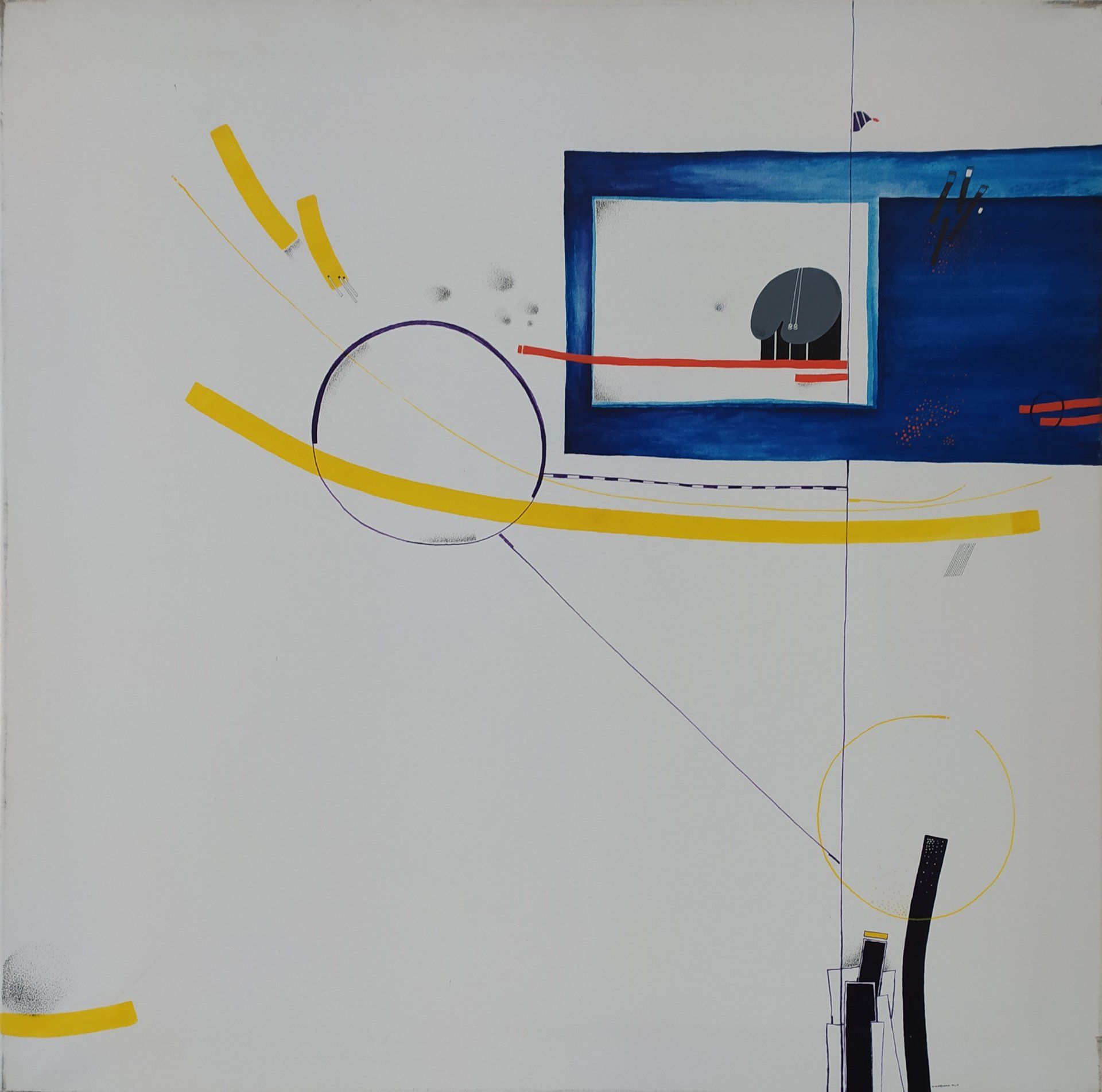

After the artist returned to Germany after about 7 years in Italy, he changed his painting style once again, and thus began the last phase (7) of his artistic work. Even in this phase, Gerald Maria Stecker by no means limited himself to only one form of expression, but one can still recognize a certain basic mental attitude that is present in all his paintings. Although his works can still be assigned to abstract expressionism, as it is already known in art history through artists such as Jackson Pollock, he now developed again, for the third time in his life, a very personal style. There is not yet an existing name for this style, so we must first try to approach such a name. He was concerned with bringing the viewer into a state of "pure seeing".

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 200cm, 1994

The first thing that stands out is a freer approach to conceptualization. Whereas earlier he had strictly identified the formation of concepts with intellectual thinking, whereby the geometricizing element also penetrated into his painting, he now became visibly aware that there must be a deeper connection between perception and concept. The strict division into pathos and ratio proved to him to be an intellectual error. Thus he noticed that there must be an original unity between perception and concept. What he had formerly regarded as a purely passive world-ground to be suffered seemed to already contain those forms which he had hitherto considered to be pure constructions of the intellect. He became aware that the human mind does not arbitrarily add intellectual forms to an irrational primordial world, but that such an irrational primordial world does not exist at all. He discovered that this objective primordial world already carries finished, intellectual primordial forms within itself, and that the concept formation of the subject can at first only consist in becoming aware of these forms. Figuratively, this is expressed in such a way that certain areas of colors and forms are delimited by thin lines. He himself called it "isolation of the bodies". The form that is created by the thin line, however, is already largely predetermined by the color areas and structures that it delimits. Nevertheless, there is always a certain freedom of interpretation in relation to what is perceived. The concrete concept formation is not already determined in advance. Thus, although the form to be recognized is already present, the delimiting concept always has a certain subjective freedom. Therefore, it can also create forms, which are not yet predetermined, by delimiting areas, in which no perception is present. One sees this in the empty fields bordered by fine lines. Furthermore, the ability to conceptualize contains the possibility of creating new structures that are not yet predetermined by perception. Here again, the artist was concerned with one of the basic themes of his life: how to create connections between people. In terms of design, this was expressed by placing isolated forms in connections with one another - what he himself called "controlled encounter." Starting in 1997, certain columnar forms began to appear more and more in his paintings. He himself saw in them a "connection between classicism and modernism".

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 250cm x 200cm

What the artist discovered here in the abstract area anew, corresponds absolutely to the spiritual-scientific facts in our daily experience of the human reality. One can understand this more easily if one looks at an object created by man, like for example a window. There can be a real window only as a unity of concept and perception. However, one must carefully observe the order in which this unity is created. One must distinguish between the creators of the window and the homeowner who sees the window for the first time when it is installed. The creators of the window, i.e. the carpenter, the glazier and the mason, cannot possibly have built and installed the window without knowing the concept of the window and being fully aware of this concept. It is quite inconceivable that a window could have assembled itself and inserted itself into a wall by pure chance. All the craftsmen involved knew the function and meaning of the window. The concept of the window therefore already existed as a thought for them before they began to build the window. Because of this concept, because of the detailed idea of the window, they only began to create it. Each of the participants knew what he had to do, because he already possessed the concept of the window as a thought. Extremely simplified, this concept looks something like this: "we cut this wood so and so, we put it together so and so, so that you can open and close the window, we add the glass panes so that they protect against wind and rain, but you can still see through, then we install the window in a certain position in the wall, which is given to us by the architect, because he knows "where the window must be installed best".

When the window is finally finished and correctly installed, then in the best case there is an absolute unity between perception and concept for the craftsmen: "the window has turned out the way we wanted it to". But when the homeowner comes for the first time, he initially has only the perception of the window. The individual terms are added to him only later. Only when he has looked at the window very closely, then he has formed most of the terms, which the craftsmen had had during the construction, in addition. Not all terms, otherwise he could have built the window himself. But he understands, for example: "the window is made of good wood, it closes well, the panes are well insulated, you have a good view, and it is at the right height". To form these different concepts, he needs a little time. The concepts rise one by one within himself as he examines the window. So they are not yet given together with the perception! They add themselves only afterwards, rising from the inside of the soul of the observer. But does this mean that the owner of the house creates these concepts himself? He would do that only if he formed other concepts than the craftsmen had been. For example, he might think: "the window could have been a little lower!" In general, however, one can say that most of the concepts he finds had already been contained in the window itself. Only the full reality of the window arises to him only by the unity of perception and concept, which means nothing else than: he must look at the window, touch it and think about it! If he would not be able to it, to form the correct concepts thinking, then the window would become for him no full reality. A small child who is not yet able to form all the concepts of a window can therefore fall out of a window, for example, because he has not yet formed the concept "if I lean out of an open window too much, I can fall down". This very concept was certainly very well known, especially to the architect, which is why he positioned it at a certain height, but children, as we know, can stand on chairs that change the height conditions. Without the necessary concepts, our perceptual content thus remains an orderless combination of sensory impressions. Only by the thinking observation of the world the full human reality results.

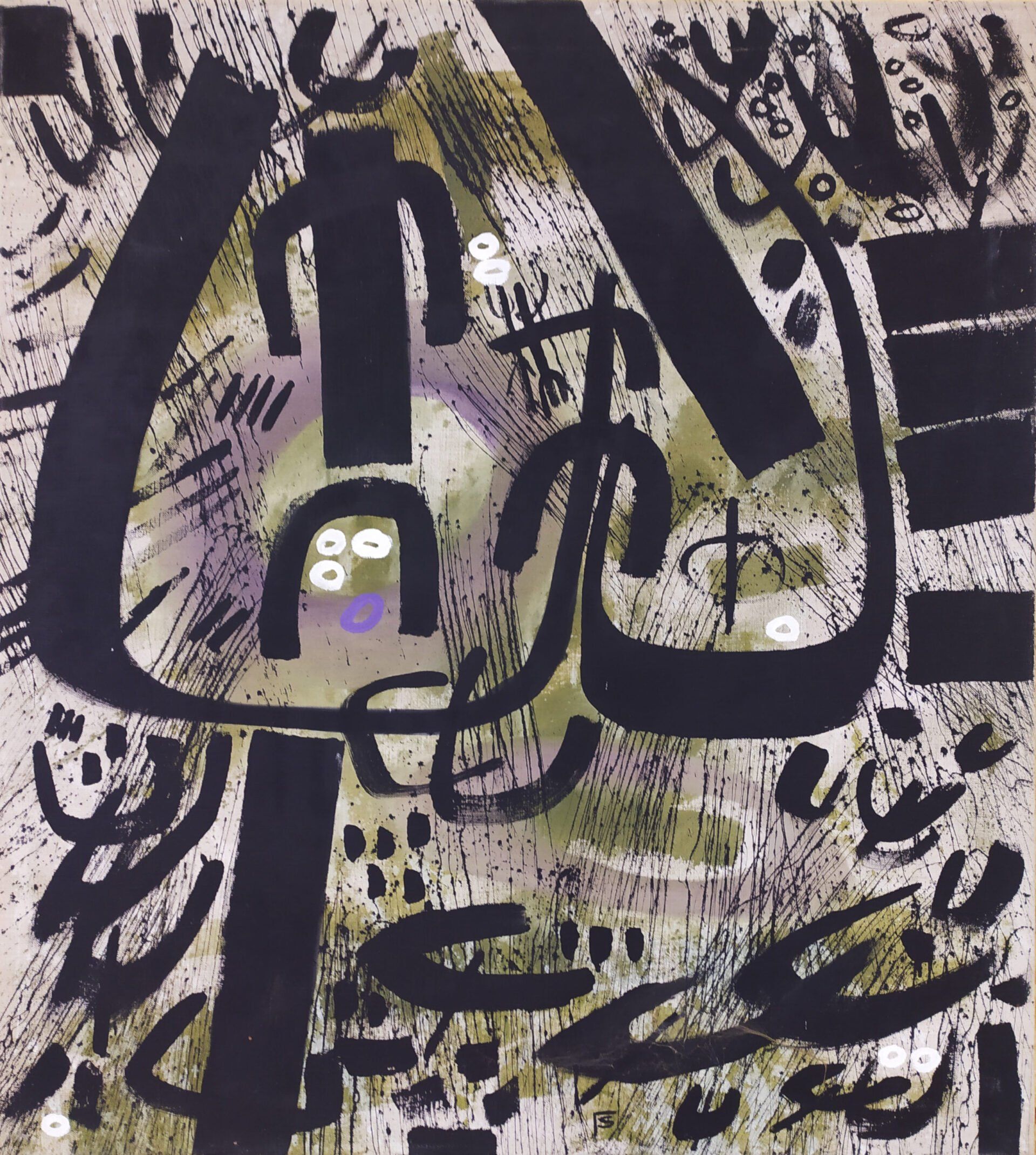

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 280cm x 200cm

So what arises in the abstract realm through the interaction of concept and perception? An abstract reality is created. Accordingly, what we see in Gerald-Maria Stecker's paintings in his last creative phase are abstract realities that originate from the artist's personal world of imagination. There would be no sense in trying to add concepts from the representational world to these realities, because it was fully consciously intended by the artist not to allow such a thing to happen. He did not want us to recognize objects of our everyday life in these colors and forms, but he wanted to guide us to learn to accept purely spiritual realities as such. If one wants to think about these realities nevertheless, then one can do it only in such a way, as it happened here. If one would want to look for transitions to the objective world, then one could do this perhaps on the basis of the "negative forms", which become noticeable, however, in 1995 in his pictures. According to those people who are capable of such cognition, physical objects appear namely - seen from spiritual world - like hollow spaces!

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 250cm x 200cm, 2000

We are hereby confronted with a fantasy world which, it is true, originates from a single human being, but this single human being was not, after all, an individual creation, but belongs to the whole of humanity, and, as a child of our time, he expressed what lives in many of his fellow human beings as well. Due to the development towards individualism, one of the main concerns of every modern artist is to express the relationship of the individual man to the spirit of the times, so that his fellow men can overcome their loneliness through the representation of a generally valid situation.

What we still owe to the painter Gerald-Maria Stecker is a new name for the last phase of his work. He himself continued to be content with the term "abstract painting". But abstract originally means: withdrawn, extracted, and indeed withdrawn from the representational world. Something that has been subtracted from reality through abstraction. This may well have been the case with Gerald-Maria Stecker. As we could understand, he abstracted his forms and colors step by step from the human world. But what he did in his last creative phase is more than such a process of abstraction. He begins here to create within this abstract world new objects, a whole new reality, which is, however, purely spiritual. It seems therefore justified to call this new way of painting Abstract Realism.

To what extent each of us considers this abstract reality justified is a personal decision. In any case, the artist here presents us with a new abstract reality that we have never seen before! What we see in his paintings is the moment of the birth of new kinds of objects. The process of representational cognition is depicted in its very beginnings, except that the very world perceived is not natural, but freely created by the artist.

To summarize the entire artistic development again: Gerald-Maria Stecker first abstracted the colorful and formal element of our perceptions out of natural reality, then created a new abstract world of color and form out of this element, and finally arrived at a point where new kinds of objects formed before him out of the abstract colors and forms. A new reality formed before him on his canvases, which is why the term "abstract realism" seems justified, even if it sounds paradoxical at first.

G.-M. Stecker, acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 200cm

Essay by Alexander Stecker, April 20, 2020